The 50th Japan Foundation Awards

―Culture Transcending Borders― <3>

A Commemorative Talk session by Miyagi Satoshi and Miyagishima Haruka (Part2)

May 24, 2024

【Special Feature 080】

Special Feature: The 50th Japan Foundation Awards ―Culture Transcending Borders―(for summary on special features, click here)

Mr. MiyagiI Satoshi, the General Artistic Director of The Shizuoka Performing Arts Center (SPAC), is an internationally acclaimed stage director who produces festive spaces on the stage through his unique fusing of physical movement, words, and music.

This article presents the content of Mr. Miyagi's lecture on "Theater that Transcends National Boundaries."

See Theater that Transcends National Boundaries (Part 1) here

Miyagi Satoshi ©Ryota Atarashi

Miyagi Satoshi ©Ryota Atarashi

Theater that Transcends National Boundaries (Part2)

- Miyagishima:

There was a question from the audience as well, asking what kind of impact theater and the work of directors has, given the current inward and exclusionary tendencies in the world. Could you please share your thoughts?

- Miyagi:

What you just said about emotions spilling out, it's not necessarily about them automatically spilling out, but more about expressing them, right? It means expressing the current emotions we're feeling, inadvertently revealing them. Once expressed, the audience feels like both the question and the answer are already apparent, and they no longer feel the need to look further.

So, one thing I'd like to mention about that is the importance of not knowing oneself too well. I believe it's crucial because when you base your identity on it, ultimately, it feels like you can't overcome human arrogance, the arrogance of modern humans. Modern human arrogance, to put it simply, is the belief that humans can control nature. In nature, naturally, oneself is also included. Because there's nothing more natural than one's own body. So, the idea of being able to control oneself and being able to control nature become integrated. The notion arises that by humans controlling nature, the potential of nature can be better realized. Rather than leaving it alone, if humans properly control it, the potential inherent in nature can be more fully brought out. Some might think that even God has intended for humans to go that far, and that's why God has created humans. From my perspective, it's an extremely arrogant way of thinking, and I can't help but think that this kind of thinking will lead to the destruction of the Earth.

From Mahabharata - Nalacharitam ©Ryota Atarashi

From Mahabharata - Nalacharitam ©Ryota Atarashi

- But as I said earlier, using the European acting mindset and mainstream European acting theory, I don't think you can break free from this. There's this arrogance that humans possess, this belief that humans can control nature. I feel like it's impossible to escape from this arrogance. And because the concept of acting itself is attached to it, you have to start by acknowledging that you don't really know yourself well, not even your own body. You'll never fully understand your own body no matter how much time passes, so I think you have to start from a place of humility.

Based on that humility, for example, when playing a "mover," it's quite similar to becoming like a bottle. Similarly, for the person delivering lines, not being able to move is also the same, and it's incredibly frustrating. For actors, not being able to move while delivering lines is incredibly frustrating. They want to move, but it's forbidden. It makes it feel like despite having a great ability, they're severely restricted and can't fully express themselves. I think that kind of constraint could be helpful in overcoming that arrogance, by grounding oneself in humility. When you think about it, traditional forms of theater and folk performances have methods and wisdom to avoid falling into that kind of arrogance, right? For example, wearing a mask. When you put on a mask, your facial expressions doesn't show.

I'm also working as a director for a public theater now, which is a bit different from discussions about theater theory. As a director at a public theater, what do I consider the most important aspect of my job? Well, I believe it's about somehow containing totalitarianism. Totalitarianism, you see, feels like it's gradually encroaching, or rather, it's already quite close, I think. In a nutshell, totalitarianism is excluding minorities, or rather, making them nonexistent. There's a term for minority "elements," like dissidents or something. It's about making these minority elements disappear. Essentially, it's exclusionary. If there are different elements present, they're either expelled or, well, assimilated in some way, one or the other. This exclusionary atmosphere is spreading in Japan too. However, I don't think it's a unique issue to Japan. It's a global trend.

For example, if the majority of people agree with a certain idea, it doesn't necessarily mean that the idea will dominate society. The fact that the majority has made such a judgment may indeed affect the government or other authorities, but that in itself doesn't constitute totalitarianism. Totalitarianism is when everything collapses like dominos when a certain wind blows. So, for instance, if a leader with dangerous ideas emerges and gains the support of the majority, it still doesn't necessarily lead to totalitarianism.

At least in the case of Japan, Japanese totalitarianism isn't led by a single leader, but rather it arises from below, from the people themselves. It's more like the idea of the "Gonin-gumi" from the Edo period, where if someone deviates from the norm, others either reject or assimilate them. That's what people do. In Japan, if even three or four people out of a hundred don't conform to the prevailing sentiment, it can lead to others questioning the norm. When everyone else thinks conforming is natural, having someone who doesn't conform can make others pause and reconsider, like, "Hmm, I thought this was the way things are supposed to be, but maybe not." So, Japanese totalitarianism from below is like everyone agreeing, "This is how things should be, right?" And everyone agreeing with it. But if there are just a few people who aren't like that, even if it's just a few, it doesn't have to be a majority, just a few, and it makes you pause and think calmly.

- This ability to pause and think calmly, I think is something that can happen in theater, in small settings like a theater or even in organizations. When everyone thinks that way and then they see a play, they might think, "Wait, theater is different. The people here are different." Of course, during such moments, there are also people who try to assimilate the theater. But within that, there are also people who might think, "Wait, I thought this was supposed to be the norm, but maybe it isn't." I think it's really important to have people who don't think it's normal. If that's the case, then even in a small, modest theater, not one with tens of thousands of people, just a few hundred, it feels like it's possible. So, when totalitarianism approaches, I think theaters become incredibly important places.

However, public theaters didn't exist in pre-war Japan, right? There were no public theaters during Japan's fascist era. If we think about where they existed in the world, well, they were in Germany. In the 1930s, there were already public theaters, but ultimately, in Germany's public theaters, they couldn't resist. They were fighting tooth and nail, but ultimately, they were swallowed up. That's heartbreaking. What I mean by fighting tooth and nail is this: For example, in the 1930s, in German public theaters, they couldn't stage plays by Jewish writers, right? They were directly banned from staging them. So, what did theater people do? Even though they stopped staging plays by Jewish writers, they thought that maybe if they staged works by Goethe or Hölderlin, people might calm down a bit. However, that didn't happen. I think about what should've been a bit different. I wonder in what way it should have been a little different, but I don't believe it was completely useless.

- Miyagishima:

Through working in a public theater and observing you up close, I can't help but keenly feel this issue. I'm not as mature as you are yet, so there are times when I easily get carried away. But I do consider deeply what I should do in such situations.

Although this is a drastic change of topic, as another theme of discussion, I'd like to talk about what we can expect from digital technology in the future of stage arts, which have traditionally been seen as the most analog form of expression.

I can't help but feel that you are a very digital person. The reason being, I first learned about various digital features from you, such as Google Photos.

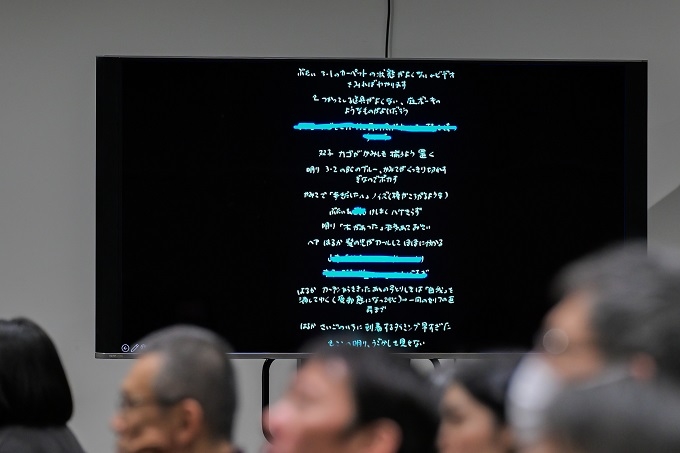

Another thing that occasionally surprises people is that after a performance, you send notes, or rather feedback, to the actors during the show. The notes highlight areas of improvement and are handwritten on an iPad. Then, they are attached to an email and shared with the cast and crew. Can you please put up the image? These kinds of notes are sent to us after every performance. By the way, my favorite note is this one, asking me to suppress my ego and be more passive, and this is how they are sent digitally.

Also, this might be surprising, but in your works at SPAC, I'm not sure exactly when it started, but once we've reached a certain point where we can run through the entire performance, all rehearsals and lectures are recorded and shared among the cast every day after each performance, and they're made available on platforms like YouTube. The production staff handles this process, and I receive these daily. It's become part of my routine to check the videos every day. I review them, noticing things like, "Oh, this part wasn't quite in sync today," or "The delivery of this line flowed well," and so on. I use them to improve rehearsals or performances the next day.

- Since my involvement with SPAC was my first job as an actor, this process of recording the videos and reviewing them each time has been crucial for enhancing the quality of the production once it reaches a certain stage. It's become quite natural for us, but I've noticed that it surprises people when we do this outside of SPAC. I personally think that both you and the SPAC theater troupe seem to be extensively utilizing the power of digital technology in creations.

We also received a question about how subtitles are presented during overseas performances. There have been various approaches taken in the past, such as glasses-like devices for subtitles.

Within the realm of stage arts, there's a certain integration between creation and digital technology, especially within SPAC. So I was hoping we could talk about this as well. Sorry, you can probably tell I don't really know a lot about digital technology, which is a bit embarrassing. But it's kind of funny that there's a part of me that can't even imagine creating without video. What are your thoughts on this?

- Miyagi:

So about the notes, which are still handwritten, directors who are around my age usually gather all the actors together when distributing notes. It's common for everyone to gather and go through each note one by one. Usually, the assistant director takes notes, and during the performance, the director might tell them to jot down certain things. Then, after the rehearsal is over, the actors gather again. This is the usual method for my generation, but I feel like it's a waste of time to gather everyone together like that. Of course, it depends on the director, but sometimes the feedback or the notes themselves become like a show. Some directors might have techniques to make actors feel like the time spent gathering was worth it. Some directors have improved those techniques, but sometimes you have to gather the staff for notes as well. Staff members have other work to do, so I thought it would be better to avoid wasting time like that if possible. I thought, why not just write them down and send them as is? The fact that theater has been conducted in the same style for 2,500 years, doesn't necessarily mean we need to stick to a traditional face-to-face format for everything just because this is art. That's how I thought about it.

Notes handwritten by Mr. Miyagi

Notes handwritten by Mr. Miyagi

- The theater group I was involved with before coming to SPAC was called " Ku Na'uka." Although it's a bit grammatically incorrect, in Russian, it means "To Science." Why was that its name? In theater, especially for our generation, there's this idea of spiritualism or this atmosphere. There is this tradition that surrounds the core essence of creation. It's something that's attached, for my generation, to each theater company, to each director. Spiritual makes it sound like a good thing, but it's actually just ambiguous, vague. This ambiguity, this vagueness, is what surrounds the core expression, the essence. It's become so commonplace within that community.

So, when it comes to that ambiguity, for new members joining a theater group, they also feel they need to embody that ambiguity. And what do they do? They end up imitating what everyone else is doing. When everyone else faces right, they face right too, so to speak. Then what happens is their acting doesn't really improve much. The reason for that is, for instance, even if someone is training, they're not really thinking about what the true goal of that training is. They just end up doing it because they see everyone else doing it that way. So, while everyone can somehow do things that seem similar, many people in my generation's theater world often lacked an understanding of "What does doing this enable me to do?"

Right in the middle of that, there's a mystery. It's something that can't be explained. That final aspect of why something is beautiful can't be explained. But surrounding that, the ambiguous, indistinct spirit can be, to a large extent, dissected into rules or things like that through analysis. It can be clarified through what we might call a scientific approach. This ambiguity, why these things are done, why they're all together, was necessary from the beginning. But somehow, over time, it became like this. So, in a sense, by using scientific analysis to figure out what was originally necessary, we could then determine how to do what was necessary. This scientific analysis could preserve the essential parts of that ambiguity while cutting away the unnecessary parts. For example, the idea that we needed to gather not only actors but also staff to give notes might not be necessary, so it could be cut away. That's the kind of thinking we had. So, this is a different dimension from what we typically refer to as digital. It's the science we talk about when we mention social sciences or humanities. That is why we chose the name "Ku Na'uka." (To Science) as the name of our company.

(Pointing to the T-shirt he is wearing) What do you think this is? This painting here is Hokusai. This was actually a t-shirt I made when we performed the play Inaba and Navajo's White Rabbit, and it is a picture of the White Rabbit of Inaba painted by Hokusai in the Edo period. What's amazing about Edo in the Edo period is that this Hokusai painting of the White Rabbit of Inaba was freely distributed as a "surimono" print, sort of like a novelty item. Since nobody kept these items, it's now only found in American art museums. They were included in newspapers and such.

But putting that aside, with the idea of digitally recording these paintings, capturing them in high resolution, I suddenly remembered something. When I had just started middle school, there was a Iwanami Shinsho book called How to View Famous Paintings, by Shuji Takashina. I used to read it avidly, but the photographs in there were rather low-quality black-and-white photos (laughs). The book roughly follow the times, starting with artists like Jan van Eyck and ending with Mondrian's Broadway Boogie-Woogie, which is at the MoMA*³. Looking back now, those photos were surprisingly low-quality black-and-white prints. And at the time when I was looking at those black-and-white pictures, I found the text interesting, but I didn't really have a strong desire to see the real thing. I wasn't sure if I wanted to see the real thing because they were such terrible pictures. I didn't particularly want to see the real thing. So, I believe the more you see these high-definition replicas, the more you might start to desire the real thing instead. That's our tendency as humans. In other words, as digital replication becomes more advanced, the value of the original might actually increase in our minds.

*³ The Museum of Modern Art

Mr. Miyagi shows a T-shirt he made for a performance of Inaba and Navajo's White Rabbit

Mr. Miyagi shows a T-shirt he made for a performance of Inaba and Navajo's White Rabbit

- According to a story I actually heard from President Kunieda of NTT ArtTechnology, when the ceiling of a temple in Obuse was publicly displayed at the "Digital x Hokusai" special exhibition using high-resolution digital reproductions of Hokusai's late-life hand-painted Phoenix Glaring in All Directions, the number of people visiting Obuse increased dramatically. In other words, the number of people who wanted to see the real thing increased significantly. It's not the case that if a reproduction is of such high quality, people might feel like they've seen it just by looking at it. Isn't that interesting? It's almost the same, you can't tell the difference. People aren't satisfied by only seeing something that looks like the real thing. They start thinking, "So what's the real thing like?" That's the interesting thing about humans.

I'm sure the same thing also happens in theater. The thing about theater is that there's a barrier to entry because you have to physically go there to see it. And only a few hundred people can be there at the same time. That's what I mean by a high barrier to entry, or rather a narrow gateway. Especially for people who live outside of Tokyo, the opportunity to access theater is very limited. That's what I mean by a high barrier to entry, or rather a narrow gateway. To address this, digital technology could allow for reproductions to be seen in libraries or even in mobile libraries so that people could watch plays in 8K resolution. If something like that were to happen, I think the number of people who want to see the real thing would increase all over Japan.

Especially for people who live outside of Tokyo, the opportunity to access theater is very limited. Instead of feeling like they understand after seeing a reproduction, people would instead want to see the real thing. I think this applies to digital technology in general. In other words, if the resolution becomes higher, you might think you don't need the real thing anymore. However, the fear that the value of the real thing will diminish is unfounded. On the contrary, the value of the real thing or the value of face-to-face interaction may increase.

For example, President Trump was said to be a master of using social media, and it's said that he won the election because of it. But in the end, it's the face-to-face speeches that matter, right? Few people emphasize face-to-face speeches as much as he does. That's why those last riots couldn't be stopped. Because physical presence is prioritized. So, no matter how much digital technology advances, I think physical value will only rise, not decrease.

However, in the world of theater, I believe there is another problem we are facing. That is, it costs money to see live theater performed by real human beings. So, even though people who have seen reproductions may want to see the real thing, the fact that it's expensive prevents them from going. This is a problem in the world right now. Essentially, the people who can see the real thing are very much, well, let's say, limited to those who are wealthy and have the means. It's becoming like a privileged hobby for those with abundant resources. Others mostly watch free videos, even when it comes to theater. This kind of two-tiered culture is happening in reality.

However, upon closer reflection, I also wonder if this is just a midway point in the process of digitalization. Currently, it does cost a lot to perform in theaters, and indeed, the ticket prices are high. The admission fees for theaters that rely solely on ticket sales are steadily increasing, which is understandable. However, as I mentioned earlier, the core part, which is highly analog, remains a mystery that cannot be tampered with. But we analyze the figures for the surrounding aspects, like money or other troublesome operations, so if it could be largely digitized, then perhaps the theater admission fees could decrease.

For instance, when we were performing at SPAC, the ticketing was quite labor-intensive. In such areas, that vague sense of spiritualism that I mentioned earlier still remains among theater folks. They consider it a value they've cherished for a long time. For example, wanting to actually see the customers' faces and hand them tickets, that sort of thing, right? It's true that it feels important, but if we were to cut costs in such areas and make admission fees cheaper, allowing more people to access theater, then weighing those options, it seems better for more people to have access. So, by further integrating digital technology into the somewhat vague theater industry, perhaps ticket prices could decrease.

From A Midsummer Night's Dream ©K. Miura

From A Midsummer Night's Dream ©K. Miura

- Another thing is that sharing the process through digital means has become much easier. You mentioned how videos are sent after each rehearsal, but 20 years ago, this would have been quite difficult. Of course, there were no video sharing platforms, and we'd have to record using VHS or S-VHS (laughs). I remember buying a camera when I was in a theater group, but I bought it on installment because it was expensive. Anyway (laughs), back then, if you wanted to watch those cassette tapes, you had to gather everyone to watch them together. Sharing this process has become much cheaper thanks to digital technology. More things like this will likely happen at various levels.

For example, there's this concept of "process economy," a term coined in Japan, or rather a kind of Japanglish term. It's about sharing the process itself and getting paid for it, and we've already started something new while working on The Rose Knight. In theater, traditionally, only the finished product was shown, and only the finished product was sold. The process in between is like a black box, a true mystery. You don't know how it can be done, and suddenly it comes out as a finished product. Showing the process in between was frowned upon and considered a spoiler, but no, that's not how it should be. Rather, it's the process of the play being made that's interesting. In fact, a play, even after opening night, continues to change towards the final performance, and is continually being created, right? So, in actuality, it's not a finished product, theater is showing the process. That's what's different about theater compared to movies or novels. They might show the process, but somehow it's presented as if it were the finished product. So, instead of that, perhaps we should consider getting paid for sharing the process itself. The concept of theater is not just about buying finished products but about community. It's not a place where finished products are sold and bought, but a community where you can see various processes through that window. This way of thinking lacks a bit of reality without digital technology.

So, it's quite surprising that theater is still performing plays written 2,500 years ago to this day. There is no other art like it (laughs). So, there's this aspect of wondering why such an old-fashioned mode of expression still exists. But as I mentioned earlier, if you carefully dissect the somewhat ambiguous nature of theater, I think you'll find that with significant digitalization, various barriers may be lowered.

From Antigone ©Stephanie Berger

From Antigone ©Stephanie Berger

- Miyagishima:

I felt both embarrassed about my lack of knowledge in digital technology and realized its importance. As someone involved in stage arts, I believe it's crucial to continually question which aspects to prioritize for face-to-face interaction and where to leverage digital technology. I think this stance will become increasingly important in the future. I've learned some very important points from what you shared with us just now.

Although I would love to hear more, it's about time to wrap up. I was wondering what your final thoughts or words of wisdom might be. Perhaps, from your perspective as someone who has been involved in theater for so long, received the Japan Foundation Award, and is now in the position of a director, what are some things you'd like to convey to young artists or aspiring theater practitioners?

- Miyagi:

If you aspire to art, focus on universality. How universal your own work is, or rather, how much universality it possesses, is the yardstick by which you gauge your own creations. It might sound odd to use the term "yardstick," but the degree of achievement in your work essentially boils down to how universal it is. That's how I've always seen it. And because of that perspective, as I mentioned in the beginning, I believe in those moments of empathy, no matter how different one's background may be. In other words, if your work remains confined to the local traditions or folk performances of the Japanese language and Japan, then even foreign audiences might say, "Japan has some unique theater." This doesn't mean that the refinement level is low. Within those local traditions, there are some incredibly refined performances, right? Some folk performances are remarkably sophisticated. But why do they fall under the category of "ethnic art"? It's because they are exotic to people outside of that region. Essentially, if it's something Japanese, it might be viewed through Orientalism. As "Oh, so this kind of theater exists too."

But as I mentioned earlier, that doesn't lead to the proof of empathy. Unless people around the world think, "Ah, this kind of theater deals with the same issues we face," they won't be placed on the same platform as contemporary art, and those moments of empathy won't occur.

From Yashagaike ©Eiji Nakano

From Yashagaike ©Eiji Nakano

-

So where does theater diverge between something like local Japanese folk performances and theater that the world sees as "contemporary world theater"? Of course, I'm using a very broad term like "the world" here, and it doesn't necessarily mean Europe. There are probably issues that everyone on the planet is facing, like COVID-19. It was rare how almost everyone on Earth was dealing with the same problem, but on a global scale, such things happen. These challenges that everyone is actually facing, for instance, environmental issues, are quite evident and easily understandable. But it's not just that. There are other aspects, like the relationship between language and body, as I mentioned earlier. This is something every human faces. The detachment between language and the body, or perhaps loneliness. Loneliness is often talked about in Japan, but loneliness is a problem that all humans face, right? This issue of loneliness is probably closely related to language.

What does it mean to be human? What is the reason for being human? What are the differences between animals and humans? There are several differences, but one of them is that language and the body are in conflict. In terms of language alone, it is said that there are animals among other species that can convey information to others. They are be able to transmit information to other individuals. However, the act of thinking in words is probably only done by humans. When we engage in thinking using words, emotions come up as something foreign. Language and things like the body or emotions, as I mentioned earlier, operate on different gears. These two things are in tension with each other, so to speak. This is a challenge that everyone faces, right? By addressing issues that are relevant to people around the world, even Japanese-language theater can become part of the global contemporary theater scene rather than a traditional Japanese performing art. So, I hope to see people work on these kinds of things.

- Miyagishima: Your last response felt like one answer to the question of "What does it mean for theater to transcend national boundaries?" There are still so many things I'd like to hear more about, but we've run out of time, so I'd like to conclude our talk here. Thank you all very much for your attention today.

The commemorative talk session can be viewed on the Japan Foundation's official YouTube channel (English subtitles available).

Related Articles

Related Events

Keywords

Back Issues

- 2025.6. 9 Creating a World Tog…

- 2024.10.25 My Life in Japan, Li…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5.24 The 50th Japan Found…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2024.5. 2 People-to-People Exc…

- 2023.12. 7 Movie Theaters aroun…

- 2023.6.16 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2023.4.24 The 49th Japan Found…

- 2022.12.27 Living Together with…